Rachel

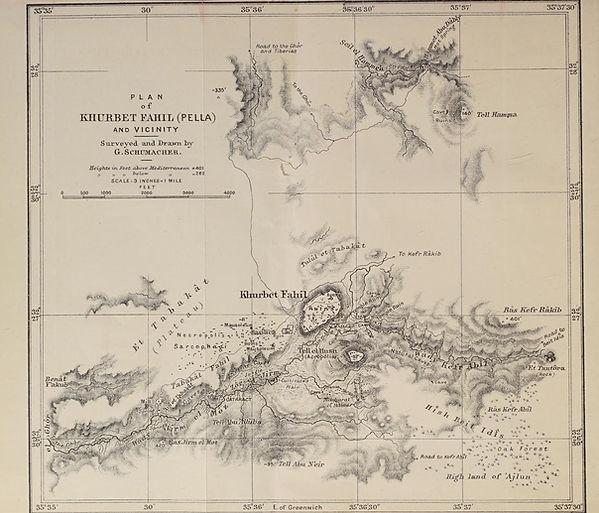

Map from Pella by Gottfried Schumacher

Oh! That the desert were my dwelling-place. –Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, canto IV

April 18, 1914

We have finally reached Pella. It took nearly two years of planning, a ten-day trip on a cruise ship from London to Port Said, a shorter trip on a steamship to Haifa, and a train ride to Beit She’an, followed by a half day’s ride on camels to get here but at last I can see the place that has become so important to me. How many nights have I dreamed of sifting soil through a sieve and finding a bead or a sherd of pottery? Some nights I dreamt of brushing away a layer of soil to reveal a remnant of an ancient mosaic or using a hand trowel to disinter a statue from its centuries-long grave. As soon as the rounded hills of Khirbet Fahil and Tell Hus’n came into view, my hands literally flexed with the desire to grab a trowel, kneel on the ground, and immediately begin to unearth the secrets of this centuries-old spot. Then I remembered who I was and the official title I bore: I was Mrs. Foster Dixon, wife of Dr. Foster Dixon, professor of archeology at Oxford University. I was not one of my husband’s archeology students; I was the unofficial and unpaid manager of this dig. While Foster’s name was attached to all the documents relating to the dig, and his wealthy father’s money had made the dig possible, it was I who had spent the last eighteen months writing to the Turkish Consulate and applying for all the necessary permits and licenses, arranging to hire Bedouin workers, coordinating travel arrangements, and making lists upon lists of what we must purchase in preparation for the dig. It was I who had spent countless days and nights making sure not a single detail was overlooked. I was willing to do all of that because Foster’s father had promised me that I would be allowed to participate in the dig in exchange for my hard work. Foster himself agreed to that arrangement while we were on British soil. As we were sailing out of Port Said, however, Foster casually mentioned that I might be so busy overseeing the practical side of the dig—making sure everyone had food and water and a place to sleep, making sure the dig was properly documented, taking care of various and sundry details—that I might not have time to participate in the dig at all.

“I’ll work on my own if I have to,” I told him stoutly. “I’ll work at night by lantern light. I’ll work on Saturdays while everyone else is resting. I’ll get up before the sun is a faint glimmer in the sky. I won’t allow you to shunt me to one side, Foster.”

“We’ll see,” he told me with a bland air of detachment, like he was lazily waving a fly away from his face. Unfortunately, I was that fly.

“We had an agreement,” I reminded him. “I said I’d document the dig and help you write up your finds in exchange for letting me participate in the dig. If you don’t, I will send word to your father that you aren’t cooperating and that I am going home—and then you’ll have to deal with all the tedious and time-consuming chores on your own.”

The look on his face then could only be described as “pettish.” Foster was a spoiled only child. He was not used to anyone telling him “No” or challenging the status quo. This more than anything discomfited him and made him wish he’d never married me.“We’ll see,” he finally said in a clipped tone. “We’ll sort things out when we reach Pella.”

And now that we had finally arrived, I knew that my threat was hollow and would not be acted upon. I had invested too much hope and longing to leave now. Even if I was pushed to the very margins of the dig, I would stay. Somehow Foster had known this even before I did.

We were in Syria, at the site of one of the ten ancient cities of the Decapolis known as Pella. Lying less than a mile to west of us was the Jordan Valley, referred to here as the Ghōr. The land closest to the Jordan River was lush and green year-round, with fields and fruit trees growing on the low-lying land. Rising above us to the east were two large hills or “tells.” The southern, higher tell was called Tell Hus’n, or “Mound of the Fortress.” Ruins at the top seemed to indicate that a fortress had been built there long ago to protect the city of Pella. The shorter, flatter hill to the north was the site of a town originally referred to as Pahil or Pihilim. When the Greeks took control of the area, they renamed the town Pella in honor of Alexander the Great’s birthplace. In 747 A.D. a violent earthquake struck this region, destroying almost all the buildings. Afterwards, the northern mound came to be referred to as Khirbet Fahil or “the ruins of Fahil.” A narrow valley called Wadi Jirm el-Moz ran between the two tells, and a spring bubbled up there year-round, providing water for the tribe of Bedouin who live nearby. Canes and reeds and tamarisks grew close to the spring, as well as eucalyptus and pistachio trees. Farther up the “throat” of the valley, the ground was littered with chunks of squared stone and half a dozen white limestone pillars that resembled the rib cage of an enormous, ancient creature poking through the undergrowth—all that remained of a Roman temple. Other, higher hills rose beyond Tell Hus’n and Khirbet Fahil, and at this time of year were still vibrant green with spring growth. By the end of the summer, most of the vegetation would be burned to the dry yellow of straw.

I could have stood and gazed at the hills for the rest of the day had not Archie Holman interrupted my thoughts.

“Well, Boss, what do you want us to do?” Holman asked, his tone blunt and matter of fact. Holman would be our cook for the next four months. He was ex-military, and was used to taking orders, and had accepted my role as the de facto director of the dig in far better stride than the rest of the male students.

“All right,” I said to the dozen students who had dismounted their camels and were looking with longing at the hills and the ruins. “I know you’re anxious to start exploring, but if you read your handbook before you left home, you know that our first priority is to set up camp.” A couple of the young men groaned, but only a couple. One, a dark, broad-shouldered man named Jonas, leaned over to the student standing next to him and said something I couldn’t hear. From the reaction of the other man, apparently it was something snide—and something said at my expense. Jonas smirked at the response.

My father had warned me this might happen. “Rachel, you’ll be the only woman in a world historically dominated—and run—by men. Don’t expect them to accept your leadership right away—or ever, for that matter.” I had naively hoped he was wrong, and now I was finding out how much smarter he was than I.

Very quickly, the camels were relieved of their cargo, tents were erected, luggage stowed, and wooden cases filled with tools carefully placed in a separate tent for easy access. Cots and tables were set up, lanterns filled with oil and hung from pegs, and two latrines were dug behind a scrim of tall shrubs—one for the men, one for me. By four in the afternoon, the camp was in order, the Bedouin that had escorted us from Beit She’an to Pella had been thanked and paid, and the students set out to explore. Foster went with them.

I wanted to explore the site, too, but I stayed behind at our camp and made sure everything was in order. My first stop was the dining tent. I believe it was Napoleon who said, “An army marches on its stomach,” and although the students weren’t soldiers, they would put in many hours of hot, dirty work over the course of summer, and I—and Holman—needed to make sure they were well-fed. I liked Holman. I found him easy to talk to. We shared the same senses of humor and practicality, plus he possessed the ability to assess a situation or problem and find unique solutions. I considered him the closest thing I had to a friend and ally here at camp.

“Holman, do you need any help?” I asked. He’d brought a young kitchen lad from England with him, and he was busy helping Holman organize his workspace. Before we left England, Holman had enlisted the aid of a carpenter friend to design packing crates that could be broken down and reassembled as tables and benches in the dining hall, thus lessening the need for us to pack furniture, which would be burdensome and costly to ship, or to purchase furniture when we reached Haifa. Another series of crates were designed to be stacked on their sides, with internal dividers serving as shelves. The crate lids were hinged on one side, which allowed Holman to close them to protect food and utensils from exposure to the elements.

“I think we’re doin’ just fine, Miss Rachel,” he said. That’s what he called me: Miss Rachel or Boss. I much preferred that to Mrs. Dixon. “I’m gonna boil some water just to be sure the stove works correctly, an’ probably tomorrow I’ll need you to go with me to the local market, but for now I think we’re set.”

Next, I made sure that Mr. Bilir was happy with his accommodations. Mr. Ihsan Bilir was employed by the Turkish Department of Antiquities. He would stay with us all summer, at our expense, to monitor the dig and to make sure that all intact artifacts we found were packed up and shipped to Constantinople after they had been logged and photographed. Mr. Bilir was approximately thirty years of age and took his job quite seriously. He met us when we got off the train in Beit She’an and spent most of the trip to Pella speaking with Foster in heavily accented English. He barely cast a glance in my direction when Foster introduced me; it was as if I were one more crate or sack to be loaded onto the camels.

“Mr. Bilir,” I said, approaching him as he stood in front of the small tent that had been provided for him. He was watching Foster and two students as they walked back and forth across a flat section of ground to the west of us, gesturing at an assortment of foot-high cubes of limestone that were scattered about the area like giant dice. Where they stood was the site of what earlier archeologists had called “the basilica” and the limestone cubes had once been part of the basilica’s immense walls. “Are your accommodations to your liking?” I asked in English. “Is there anything you require?”

He was a slender man of medium height, with an even-featured face, dark brown hair, and a neatly groomed mustache and beard. There was a faint scimitar-shaped scar on the outer edge of his left eyebrow. When he looked at me, his dark eyebrows slanted toward his nose in a fierce scowl.

“I would prefer to discuss my accommodations with Dr. Dixon,” he told me frostily. I don’t deal with mere women was what he really meant.

“I understand,” I said as graciously as possible. “If Dr. Dixon is unavailable in the future, I hope you know that you can speak to me, and I will be happy to pass along your concerns.”

I inspected the two larger tents where the students would be staying next. Six cots had been lined up, three per side, and beside each bed stood a wooden crate that would serve as a nightstand or even a desk. Suitcases were stowed beneath the cots, and as they had been warned in their field handbook, every suitcase possessed a sturdy lock. While theft was unfavorably looked upon by the native Bedouin society, guidebooks cautioned against leaving valuables out in the open and providing unnecessary temptation. I was pleased to see that the students had done as I had asked. Well, what Foster had asked. They were under the false impression that Foster had written the handbook, not I. Perhaps that was why they had adhered to “his” directions so closely. None of them wanted to be sent home for disobeying camp rules.

A large work tent—twice the size of the dining tent—was set up next to the “dormitories,” equipped with yet more tables and benches. Close examination and documentation of whatever we found during the dig would occur in this tent. Photos would be taken, sketches made, detailed notes recorded. Many hours would be spent in this tent, sheltered from the sun during the hottest part of the day.

The last tent in our little village was the tent that Foster and I would share. It was furnished with two cots, a single shared crate as a nightstand, two kerosene lanterns, and two packing crate desks. Privacy would be a luxury here at the dig; we would work together, eat together, and undoubtedly get on each other’s nerves together. I was fortunate that I had a space of my own where I could retreat from everyone else for a little while.

Foster and I were considered a novelty of sorts. It was rare for a woman to accompany her husband to an archeological site; it was even rarer still for a woman to take active part in a dig. No doubt some of the men, possibly all of them, wondered if Foster would treat me more deferentially than they, or if we would have marital spats or be inappropriately amorous, and if I could have allayed their fears ahead of time, I would have. I would have told them that Foster married me only as a matter of convenience and convention; he did not love me in the slightest, nor was he attracted to me physically. Truthfully, Foster was incapable of loving anyone but himself.

What Foster did admire were my organizational skills, my head for numbers, and my ability to pack many items into a small space. He also appreciated the fact that I could speak fluent Arabic. That particular skill would make life much, much easier for him when dealing with our Bedouin workers. Beyond that, I wasn’t quite sure how Foster viewed me—perhaps I was like a pesky stray dog whose presence he felt he had to tolerate even though he did not particularly like dogs. My true value to Foster was less tangible but vastly more important: By marrying me, he had acquired a certain propriety that had previously eluded him. In British society if a man of good breeding had not married by a certain age, questions began to arise, and assumptions regarding his sexual orientation were whispered behind his back. Now that Foster had married me, those questions would forever be silenced and his reputation would be safeguarded.